Only One Big Economy Is Aiming for Paris Agreement’s 1.5C Goal

Feb 11, 2025 by Bloomberg(Bloomberg) -- Seven of the 10 world’s largest economies missed a deadline on Monday to submit updated emissions-cutting plans to the United Nations — and only one, the UK, outlined a strategy for the next decade that keeps pace with expectations staked out under the Paris Agreement.

All countries taking part in the UN process had been due to send their national climate plans for the next decade by Feb. 10, but relatively few got theirs in on time. Dozens more nations will likely come forward with updated plans within the next nine months before the UN’s annual climate summit, known as COP30, kicks off in Brazil.

The lack of urgency among the more than 170 countries that failed to file what climate diplomats refer to as “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs) adds to concerns about the world’s continuing commitment to keeping warming to well below 2C, and ideally 1.5C, relative to pre-industrial levels. Virtually every country adopted those targets a decade ago in the landmark agreement signed in Paris, but a series of lackluster UN summits last year has added to a sense of backsliding. US President Donald Trump has already started the process of pulling the world’s second-largest emitter out of the global agreement once again. Political leaders in Argentina, Russia and New Zealand have indicated they would like to follow suit.

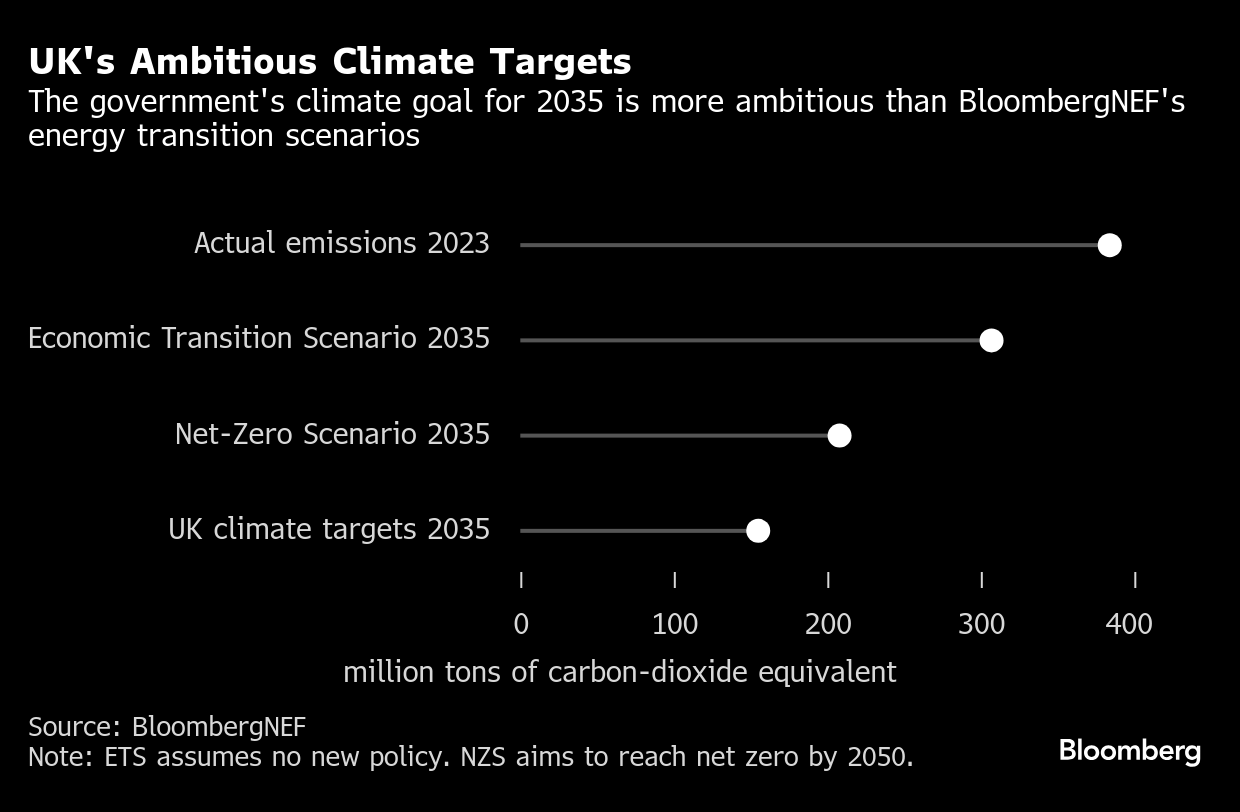

That makes the UK a rare bright spot for its continued pursuit of 1.5C against a backdrop of inflation and worries over the cost of the green transition. Its pledge to cut carbon emissions 81% by 2035 relative to 1990 levels is the only national plan so far that’s anywhere close to consistent with the Paris target, according to analysis of major emitters by Climate Action Tracker. British Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s government now must prove its climate ambitions are viable and in line with economic growth.

At the same time, the UK will hope to see other countries follow its path. The European Union, a major green power player, has yet to send in its NDC. Neither has China, the world’s largest emitter. The UN said most countries will likely do so before the end of the year.

The UK has historically been a leader in climate diplomacy, becoming one of the first large economies to commit to a legally binding net-zero target and creating an independent watchdog that held the government accountable for its climate goals. Changes in political leadership have not stopped the UK from meeting each of its five-year carbon budgets over the past 15 years.

The country “sees itself as a little bit of a shining beacon when it comes to climate policy,” said Sam Alvis, associate director for energy security at UK think tank IPPR. The anti-climate movement had very little sway in Britain’s national elections last year. The lesson for other countries on climate policy is “you can do it successfully and be politically rewarded for it.”

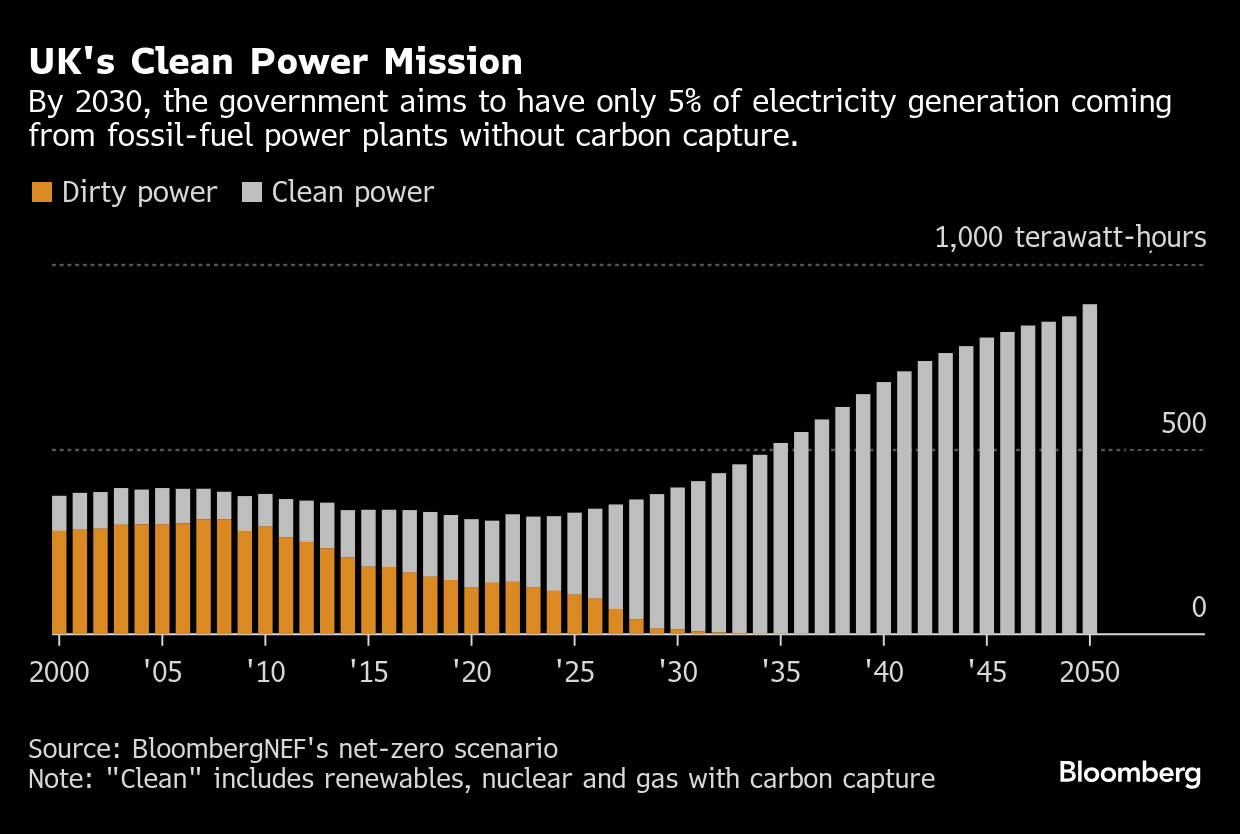

The UK’s biggest success so far has been removing coal from the power grid, a first for a G7 nation. It’s now trying to repeat a similar sort of trick for natural gas, a much tougher task.

“Cleaning up the power system early is the very best way for us to demonstrate that as a government we are even more committed to our climate objectives because we are focused now on delivering them,” said Chris Stark, head of the UK’s mission for clean power by 2030, in an interview on Bloomberg’s Zero podcast.

Britain will first need much more clean power from sources such as wind and solar. And in order to still run some natural gas plants after 2030, the government is planning to rely heavily on carbon capture technology by directing nearly £22 billion ($27 billion) towards it over 25 years. A Parliament committee this month described the strategy as risky and expensive.

Even if capturing carbon works at scale, simply cleaning up the power sector won’t be enough to meet the new British climate goal. As the UK’s NDC indicates, emissions reductions after 2030 will have to come from consumers moving to electric cars and heat pumps. There are policies in place to make this happen. But the rollout so far has been behind schedule, particularly for heat pumps.

“Selling millions and millions of these devices is no joke,” said Emma Champion, head of regional energy transitions at BloombergNEF. “Between 2030 and 2035, the UK’s climate goal is not pushing into the realm of impossibility. But it very quickly becomes a real challenge.”

Moreover, all of this has to be done during economically challenging times. The world is still reeling from soaring energy costs after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and Trump’s threats of full blown trade wars hang in the balance.

Britain’s economy, meanwhile, has grown more slowly than expected. After the center-left Labour government was elected last year, it said it would need to fill a multi-billion-pound black hole in public finances. To speed up growth, Chancellor Rachel Reeves recently signaled the government would support the controversial expansion of airports around the country and suggested it may allow oil and gas projects to go ahead in the North Sea.

While both policies appear at odds with rising climate ambitions, Reeves insists there is “no trade off” between the pursuit of economic growth and the UK’s desire to decarbonize. The test will come from developing technologies like sustainable aviation fuel and carbon capture at a rate that keeps pace with the government’s longer term goal of reaching net zero by 2050.

To be sure, the UK’s climate plans have skeptics. Even the largely approving Climate Action Tracker analysis found faults in the country’s NDC. For instance, the UK allocates a disproportionately large share of the rapidly diminishing global carbon budget to its citizens and doesn’t offset this with enough financing for developing nations to help them reduce their emissions. Just this week India said it needed more finance aid to boost its climate goals while taking several more months to submit an NDC.

Still, the UK is ahead of its peers, setting a bar that others have so far failed to meet, even as the urgency grows. “The public is entitled to expect a strong reaction from their governments to the fact that global warming has now reached 1.5C for an entire year, but we have seen virtually nothing of real substance,” said Bill Hare, chief executive officer of Climate Analytics, one of the organizations that helps run Climate Action Tracker.

Among the 2035 plans that met the UN’s deadline, the US climate goal — formulated under former President Joe Biden — is now effectively defunct. United Arab Emirates, host of the COP28 climate summit, released a proposal to cut emissions by at least 47% on 2019 levels; it was deemed “not credible” by Climate Action Tracker due to a lack of supportive domestic policy.

Brazil, which will lead COP this year, pledged to slash its emissions by at least 59% compared to 2005. But the plan lacked detail on how much its enormous carbon sinks like the Amazon rainforest will help with that effort, according to Climate Action Tracker.

Aruna Sharma, a development economist and former Indian government official, warned countries that have yet to submit their plans to take the process seriously. “Leaders must not treat this process as a box-checking exercise,” she said. “Weak plans mean a bleak future, plain and simple.”

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.

By