Trump Throws the Electric School Bus Transition Into Chaos

Apr 16, 2025 by Bloomberg(Bloomberg) -- From Rapides Parish, Louisiana to Oakland, California, tens of thousands of school children are participating in an electric bus revolution sparked by billions of dollars in federal funding.

Under the Trump administration, this EV transition is starting to stall.

In late January, President Donald Trump paused all awarded federal funds for clean school buses as part of a government-wide spending freeze, spurring a wave of delays and change of plans along the electric bus supply chain.

Though the Environmental Protection Agency, which is in charge of distributing the bus funds, has since started to release some of the money, the process has been slow-going and disruptive, according to interviews with more than a dozen bus advocates, makers and dealers, and officials from school districts and states. It’s also unclear whether the agency will offer an additional $2 billion dollars or so allocated by Congress for clean school buses that have not yet been awarded.

The EPA says it “is not blocking any recipients from receiving funding” already awarded, but declined to comment on its plans for unspent resources.

Every time a school chooses diesel over electric it locks in higher carbon dioxide emissions for 12 to 15 years, the common lifespan of traditional school buses. It also extends children’s exposure to toxic tail pipe emissions. For bus makers, meanwhile, a slowdown in orders could set back their budding electric business.

While advocates are pushing to get all of the federal funds spent, they’re also turning to states, utilities and others for the needed cash to electrify the school bus fleet, the country’s largest transit system.

“Our goals have had to change, given the new administration,” says Susan Mudd, an electric bus advocate at the Chicago-based nonprofit Environmental Law and Policy Center. “This will slow the transition. There’s a lot of hope that it won’t stop it.”

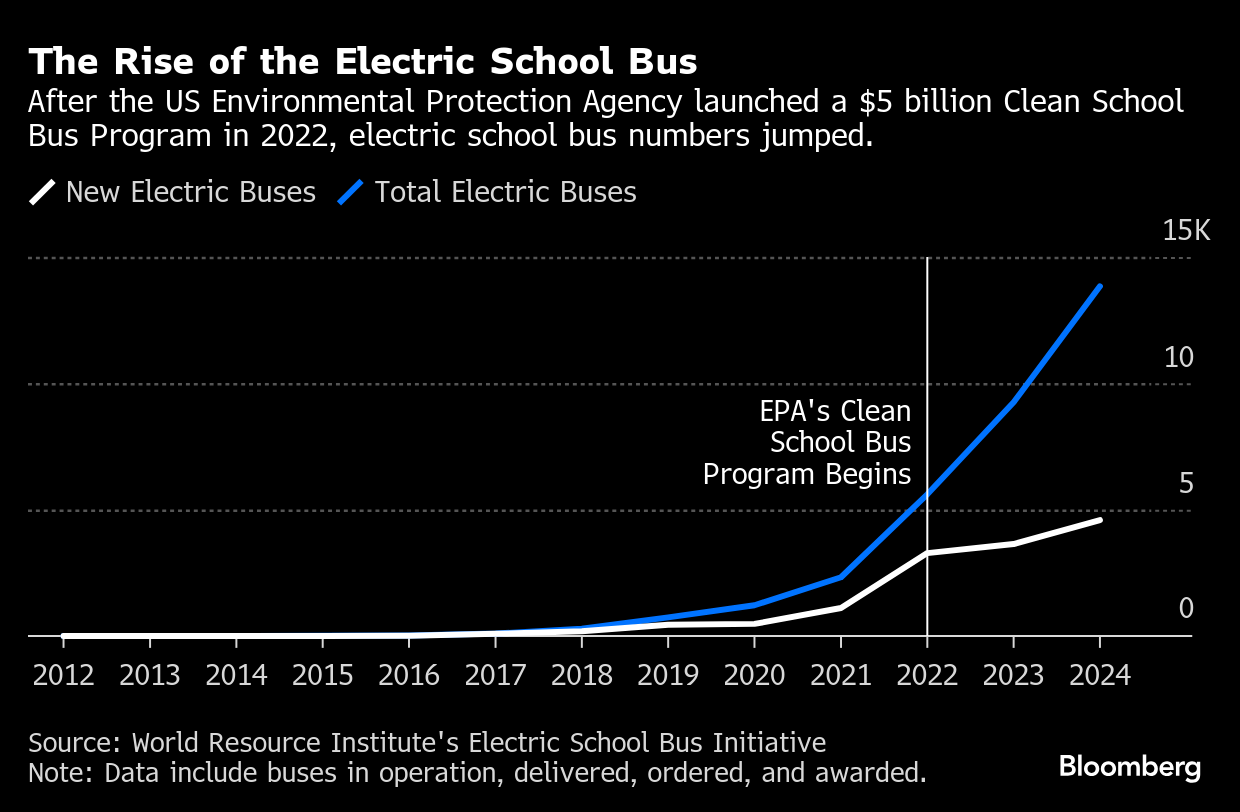

Electric school buses barely existed a decade ago. The technology got its first big break in the form of Volkswagen AG’s 2016 multi-billion dollar settlement with U.S. environmental officials for knowingly selling nearly 600,000 diesel cars that violated Clean Air Act standards, explains Mudd.

Environmental lawyers crafted the settlement money so it could go towards cleaner transportation infrastructure, offering the perfect opportunity for schools to test out electric buses without the high upfront costs, says Mudd.

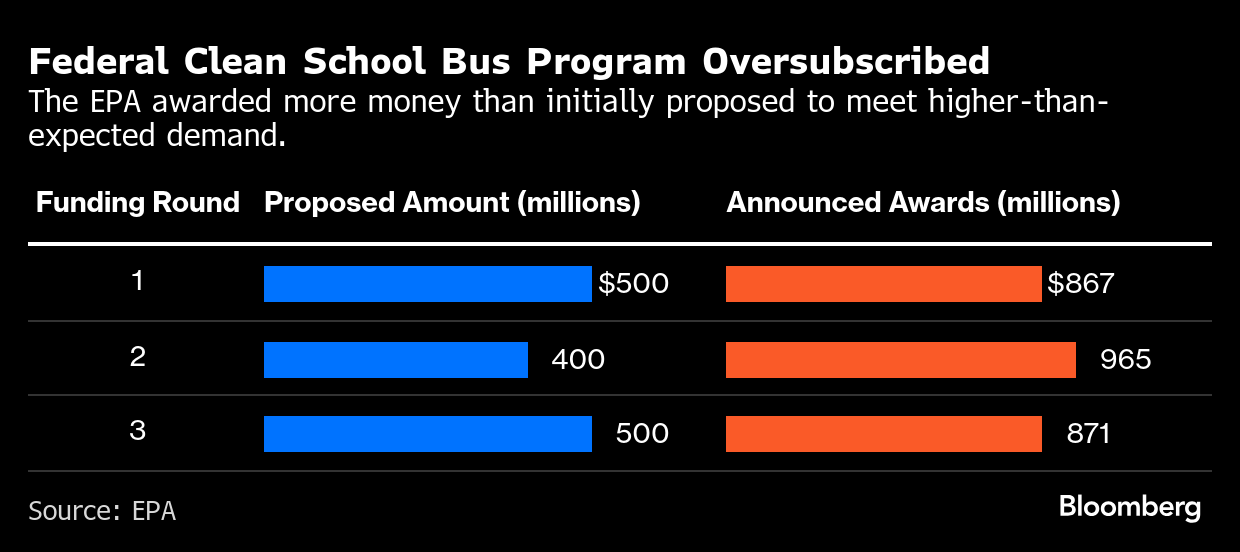

In June 2017, her team toured a rented electric school bus through Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio. Due to the lack of widespread charging infrastructure at the time, “we had to pay a diesel truck to move the bus between cities,” she says. The campaign paid off: All four states spent some of their settlement money on the buses. So, too, did other states, resulting in the purchasing of around 750 electric school buses, according to tracking by the World Resource Institute’s Electric School Bus Initiative.But that was not enough to spur mass adoption of electric buses, bus advocates realized. They found an ally in then-California Sen. Kamala Harris, who in 2019 proposed a bill to establish a federal program supporting cleaner school buses. It didn’t pass, but a few years later the Biden-Harris administration launched something similar: the EPA’s $5 billion Clean School Bus Program.It’s hard to overstate its popularity. When the agency opened its first round of applications for $500 million in 2022, applicants requested nearly $4 billion for over 12,000 school buses, says Katherine Roboff, deputy director of external affairs at WRI’s bus program. In response, EPA awarded more than planned: $867 million.

Although the number of ordered and delivered electric school buses still represent a tiny fraction — nearly 3% — of the overall fleet of nearly half a million, they’ve been selling at a rapid clip. The market share for large electric school buses jumped from about 2% in November 2022 up to a high of nearly 16% two years later, according to Ben Sharpe, a senior policy analyst at EV research group Atlas Public Policy.

Electric buses’ potential to cut carbon emissions depends on the kind of electricity used to fuel them — districts running on renewable power will get more savings. Still, based on the average electric grid in the US, a diesel school bus emits about 3.3 pounds of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) per mile, more than double the per-mile footprint for an electric one, according to calculations by the Argonne National Laboratory.

So far, the EPA Clean School Bus Program has awarded $2.7 billion across three funding rounds to buy more than 8,800 buses, most of them electric, across some 1,200 school districts. (Under the Inflation Reduction Act, the agency got another $1 billion to fund cleaner heavy-duty vehicles, most of which it has so far awarded for electric school buses.)

“As a large district with limited funds in central Louisiana, we would have not pursued the amount of money it takes to purchase an electric bus,” says Jeff Powell, superintendent of Rapides Parish School Board, which received a roughly $9.8 million EPA award. So to be able to get 25 of them in one go “essentially for free for our local taxpayers — it created a great opportunity for us,” he adds.

Putting electric buses on the road is no simple feat, requiring building out charging infrastructure, connecting with utilities and retraining drivers and others involved in bus operations. This means it can take months, even years, for schools to spend all the awarded money. So some school officials and third-party contractors that hadn’t fully spent their EPA awards by the time Trump rolled out the government-wide funding freeze. Two judges ordered the administration to release the money, but it didn’t do so immediately, leaving schools and the companies helping them electrify buses in a lurch.

After winning a $9.8 million Clean School Bus grant to cover 25 electric buses in 2023, Little Rock School District was about to start updating its bus yard to accommodate electric buses in early February. Then its EPA grant was frozen.

“We did not have the money to pay for these buses,” says Linda Young, the school system’s director of grants. To her relief, the EPA released the funds on Feb. 19 and the district was able to proceed with construction. The buses, which will transport special-needs students, are slated to arrive by the end of April and go into operation by the fall.

Rather than face the uncertainty, Plum Borough School District in Pittsburgh decided in February to scrap its electric bus plans, according to the district’s Superintendent Rick Walsh.

Companies started changing plans, too. Blue Bird Corp., a Georgia-based school bus manufacturer, said in a Feb. 5 earnings call it was prioritizing production of fully-funded electric buses and pushing back build dates for ordered buses that were supposed to be funded with the frozen money. A spokesperson for another electric bus maker, Thomas Built Bus, Inc., said the company is “closely monitoring and evaluating the situation.”

Some winners of EPA’s third and latest round of awarded funding – rebates announced in 2024 – have started to see the money, according to bus advocates interviewed by . In recent days, others have gotten notices that the money may soon be on the way. The EPA says it’s distributing rebates to award winners “who have passed quality assurance, including the approval of nearly $90 million in pending requests for use in school districts in 22 states across the country as recently as the end of last week.”

First Student Inc., the nation’s largest contractor of school buses with operations in 43 states, has been waiting for Clean School Bus rebates totaling some $216 million for 732 electric buses, including another 25 electric buses for Little Rock schools. Last Friday, the EPA sent the company what’s called “notice of approvals” for about a quarter of its rebates, a key step before funds are released.

“We’re watching our account associated with the program to monitor for deposits,” says Kevin Matthews, First Student’s head of electrification. (No money had been deposited as of Wednesday morning.)

Before the funding freeze, the company had set a goal of electrifying 30,000, or two-thirds, of its 46,000 school bus fleet by 2035. By that point, it had predicted, buying and running an electric bus would be as cheap as diesel one. The company hasn’t recently re-run its models. “Our message is: This is not an experiment,” says Matthews. “This is the better way to do student transportation and it’s here today.”

Despite the award disruptions, there are alternative sources of electric school bus funding. “We’re tracking about $2.3 billion of subnational funding for which electric school buses are eligible,” says WRI’s Roboff.

Even before Trump took office, states like New York and California had spent hundreds of millions of dollars on electric and other types of zero-emission school buses and their related infrastructure. Both of them set goals for all new in-state school bus purchases to be zero-emission vehicles — by 2027 for New York and by 2035 for California.

Overall, California has invested about $1.3 billion for 1,100 zero-emission school buses already in service statewide and an additional 1,000 or so coming into operation soon, says Manuel Aguila, an air pollution specialist involved in school bus funding at the California Air Resources Board.

California officials have been closely monitoring what happens to the Clean School Bus program under Trump’s EPA. “Obviously, we do hope it continues because we definitely want to make sure that they receive the funding to purchase more zero emission school buses,” says Aguila. “But if that does end, we will try to see what we can do to assist the school districts better.”

State electric bus programs aren’t exclusively a coastal phenomenon: In 2024, Michigan launched one to award $125 million, while Minnesota set aside $13 million. Both states plan to announce initial award winners this year.

Some utilities have also provided funding and technical help, including ComEd in Illinois and National Grid in Massachusetts, says Environmental Law and Policy Center’s Mudd. Expanding state and other programs could help fill funding gaps left by the Trump government, helping push forward the school bus electrification, she says.

Boston Public Schools got its 40 electric buses without EPA help, says Jacqueline Hayes, the school district’s deputy director of transportation. The school system has another 100 or so buses coming by next year, only some of them paid for with federal funds, and aims to fully electrify its fleet of 750 buses by 2030.

“I’m not an engineer. I’m not a scientist,” Hayes says. Her advice to other school district officials: “If I can figure this out, you can.”

(Updates with details on California school bus funding in 29th paragraph.)

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.

By