Zambia, Zimbabwe Court Investors to Revive $5 Billion Hydro Dam

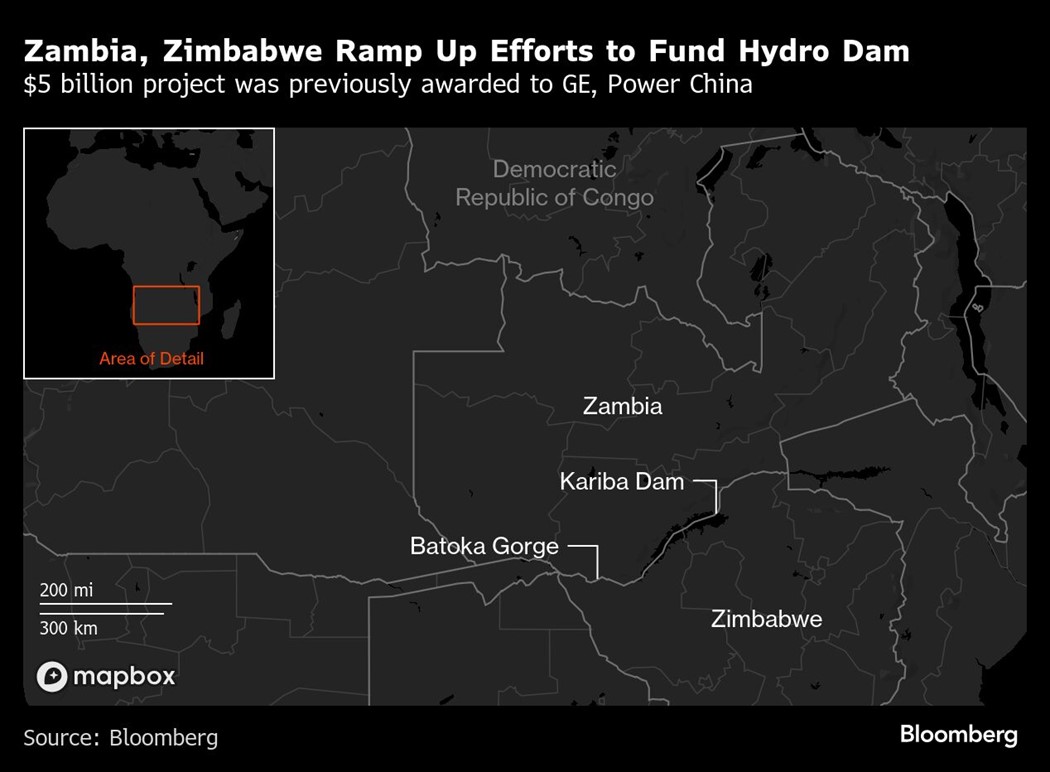

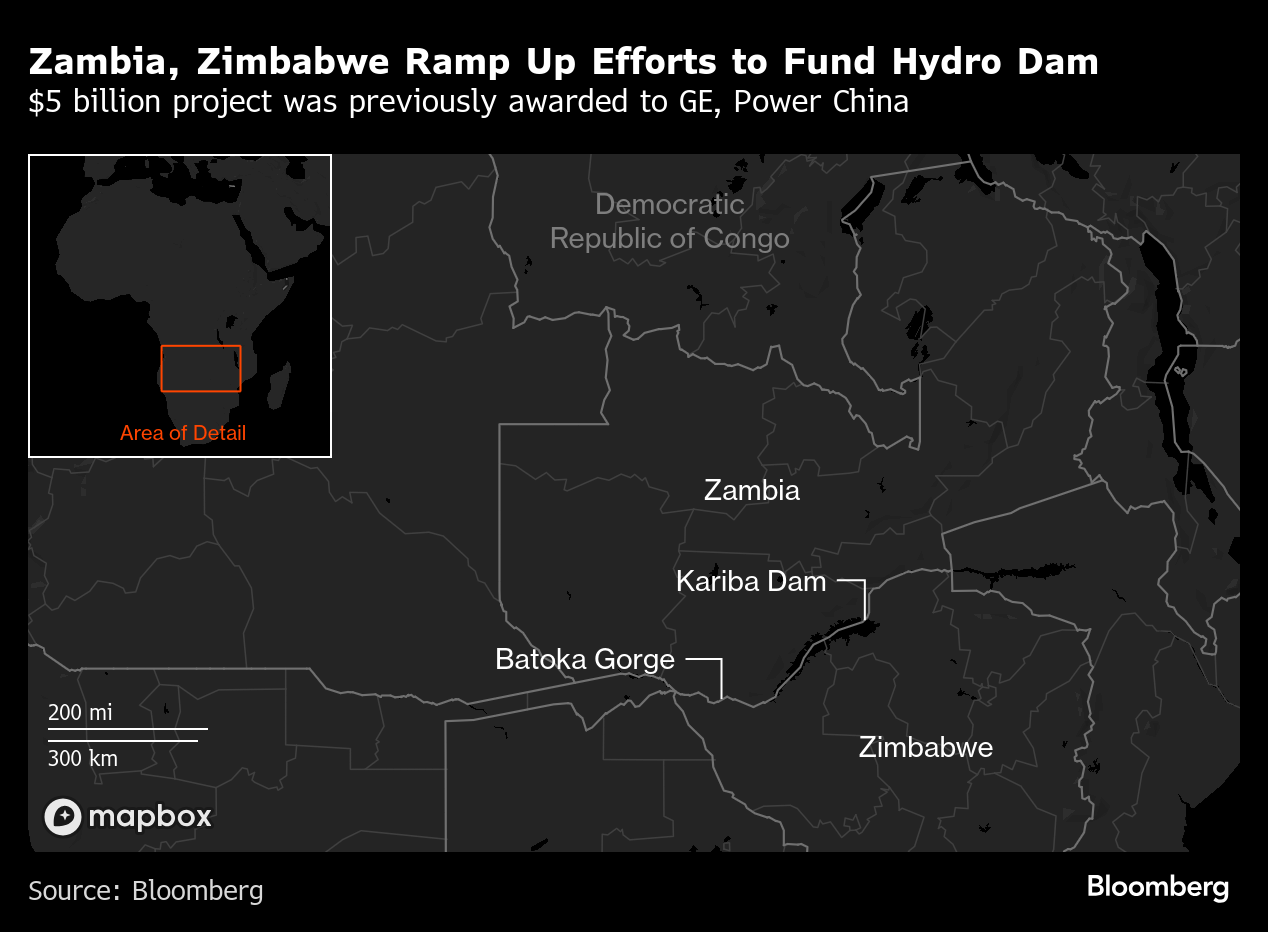

May 02, 2025 by Bloomberg(Bloomberg) -- Zambia and Zimbabwe are ramping up efforts to secure investment for the long-delayed $5 billion Batoka Gorge hydropower project, as they revive a controversial plan to potentially source water from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The Zambezi River Authority — a joint venture between the southern African nations that maintain the Kariba Dam complex — formed a team that will court investors in the proposed 2,400-megawatt facility that lies near World Heritage site Victoria Falls, Chief Executive Officer Munyaradzi Munodawafa said.

“The resource mobilization effort is targeting a time-frame of 12 to 18 months, subject to investor confidence, market conditions, and ongoing bilateral support from the Governments of Zambia and Zimbabwe,” he said in an emailed response to questions.

Work on the Batoka Gorge project had been scheduled to start in 2020, before being delayed by the onset of the coronavirus pandemic and difficulties in securing funding. Last year, Zambia announced its withdrawal from a 2019 contract previously awarded to General Electric Co. and Power Construction Corp. of China, citing irregular procurement methods.

The two countries previously set a deadline of selecting new bidders by September this year. Efforts to raise funding face further obstacles: both Zambia and Zimbabwe are currently in debt distress, with Zimbabwe owing $21 billion to creditors and Zambia still finalizing a restructuring after defaulting on its loans five years ago.

“It may be very expensive to mobilize for both countries,” said Prosper Chitambara, a Harare-based economist. “The costs will be on the high side given the debt distress both Zambia and Zimbabwe are facing.”

To bolster Kariba’s capacity and counter the effects of erratic rainfall caused by climate change, the two nations are also weighing a plan to divert as much as 16 billion cubic meters (4.3 trillion gallons) of water annually from the Congo River. While that might stabilize inflows into Kariba, challenges remain, including the high energy demands of pumping water uphill and topographical constraints.

“Detailed feasibility studies, including technical, environmental, and economic assessments, will further guide the determination of implementation time-lines and cost estimates,” Munodawafa said. Passive gravity-fed or canal systems are being considered as alternatives to energy-intensive pumping.

Inflows into Lake Kariba, the world’s largest man-made reservoir, have dwindled because of El Niño-induced droughts, threatening energy reliability in the two mining-intensive nations. Both countries have also, on a regular basis, drained the dam by exceeding their allocations from the authority of how much water they are permitted to put through the power turbines.

The lake currently supplies about half the electricity needs for both countries.

“Regarding funding, climate-related financing mechanisms are being explored,” Munodawafa said.

Experts have previously cast skepticism on a suggestion by a Zambian official six years ago that water could be fed from the Congo River — the world’s second-biggest river by volume — to the source of the Zambezi River in northwestern Zambia via canals. The Zambezi is the main source of water for the Kariba dam.

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.

By